- Spring 2020

War Eagle Road

Tim Arnold, a 1994 Auburn engineering alumnus, had the idea to put America’s newest musical road on Auburn's campus.

Drivers can now experience the first seven musical notes of Auburn’s fight song, “War Eagle” as they head toward campus. The section of South Donahue Drive is dubbed “War Eagle Road” and is located on the northbound lane between Len Morrison Drive and West Sanford Avenue in Auburn, Alabama.

Rumble strips are typically placed at the edge of a road to alert drivers, and in most cases, are anything but pleasant to the ear—but with some reverse engineering, these vibrations can create distinctive frequencies that simulate musical notes and, in a sense, perform a musical composition.

“The concept is really kind of complex and simple at the same time,” said Auburn alumnus Tim Arnold, who had the idea to put America’s newest musical road on Auburn’s campus.

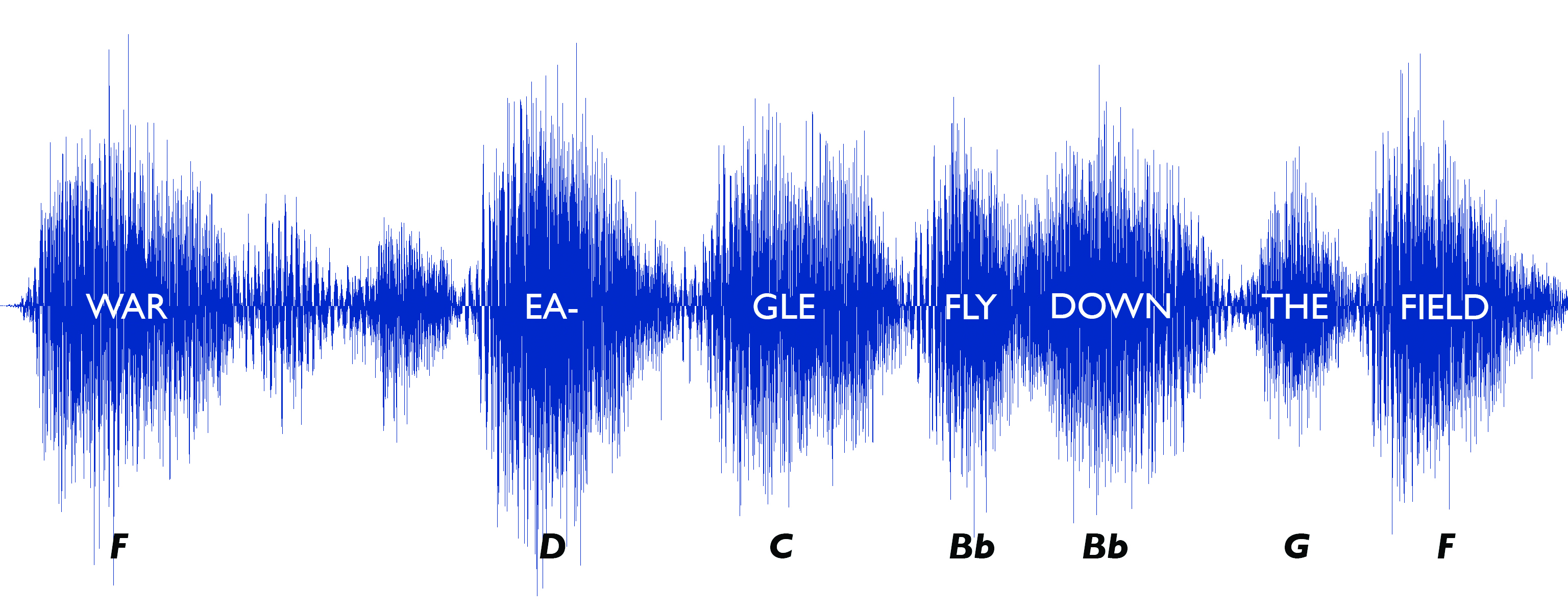

In pure physics terms, sound is vibration going through matter, and a musical note is comprised of sound vibrations at a particular frequency. An ‘A’ note, for instance, vibrates at 440 hertz. Figure 1 is a waveform of the first seven notes of the “War Eagle Fight Song”, highlighting the iconic words and their corresponding notes. A complete mathematical model is used to determine the exact number of elements and necessary spacing on the roadway to make the right frequency of each note. An automobile driving across these physical disruptions in the road can then recreate a musical tune via the vibrations, which can be heard in (and around) the vehicle. Hearing the musical road is a bonus for traveling the roadway safely at the posted speed limit.

Figure 1. War Eagle fight song waveform.

There are only a small number of musical roads around the world. The first was created as an art project in Denmark in 1995 and featured raised pavement markers to produce sound. Two other musical roads in America, created in 2008 and 2014, both used grooves in the pavement.

Arnold wanted to develop an improved method that would fit the project’s requirements of strength and durability while being safer, more durable, better sounding and, of course, non-destructive. Working with NCAT, Arnold tested DOT-approved marking tape affixed to the pavement surface on an auxiliary road at the Test Track. After determining that trial tape could work in the field, it was tested under simulated traffic conditions. Accelerated laboratory friction testing equipment—developed at NCAT—was used to test two additional adhesive tapes. The lab results indicated that the adhesive tapes could last between 11 to 18 thousand revolutions in the NCAT Three Wheel Polishing Device, which is roughly equivalent to 33 to 54 thousand single tire passes.

While initial field tests of the material were conducted at South Donahue’s 45 mph speed limit, the speed limit was reduced to 35 mph when the road was changed from four lanes to two with a center turn lane and added bike lanes. Arnold recalculated the math based on the lower speed and tested new pieces.

With new calculations and testing complete, 36 pieces were produced and cut. Arnold and colleagues from Facilities Management and engineering helped adhere the pieces to a section of the northbound lane on October 24, 2019. By utilizing materials intended to meet or surpass the current standards of road markers, costs are kept low and production and installation of the musical road is simple and repeatable.

Figure 2. A trial pre-cut adhesive material installed at the NCAT Test Track to reproduce the sound and frequencies of two musical notes.

Arnold already has a patent on this idea of creating a surface-applied material that is fabricated prior to road installation—locking in accuracy of the calculations and reducing the chance for error—and he is currently working to market this to other customers with additional potential applications.

“I’m hopeful that many other universities and towns large and small will be excited to celebrate their local culture with a musical road of their own,” he explained. “The driver-awareness and safety and qualities might also prove valuable to state departments of transportation, school or hospital zones, and construction crews who could benefit from the semi-permanent, non-destructive characteristics of the application.”

War Eagle Road is the first musical road with the surface application material, the first on a college campus and first with a fight song. Lancaster, California’s roadway plays “The William Tell Overture,” while the section of Route 66 in New Mexico plays “America the Beautiful.”

For more information about this article, please contact Fabricio Leiva.