- Fall 2016

Quantifying Pavement Albedo

Albedo is a measure of how much solar energy is reflected by a material. Pavements with lower albedo tend to absorb more solar energy, resulting in higher pavement temperatures, whereas pavements with higher albedo typically absorb less solar energy, resulting in cooler pavement temperatures. Temperature-related asphalt pavement distresses such as rutting and fatigue are influenced by pavement albedo. To account for this, mechanistic-empirical design performance prediction models include thermal property inputs such as solar absorption. On a broader scale, pavement temperature plays some role in the urban heat island effect.

Albedo is computed as the ratio of solar energy reflected to solar energy received, and therefore is a unitless value. A material with high albedo (a value closer to 1) reflects more solar energy, whereas a material with low albedo (a value closer to 0) absorbs more solar energy. Typically, a lighter color is more reflective than a darker color. Thus, newly constructed concrete pavements have a higher albedo than newly constructed asphalt pavements. However, as pavements age, albedo changes—concrete pavements usually darken over time, decreasing their albedo, while asphalt pavements typically become lighter, increasing their albedo. Pavement albedo is also affected by material properties, including the type of aggregate used.

This FHWA-sponsored study focused on quantifying pavement albedo for both concrete and asphalt surfaces. The research team—the National Concrete Pavement Technology Center at Iowa State University and NCAT—took field measurements in seven states and used the results to develop predictive albedo models relative to pavement type, surface age, and aggregate color.

Testing locations were geographically distributed and selected to include pavement containing dark and light aggregates. Sites included Cape Girardeau, Missouri; Waterloo, Iowa; South Bend, Indiana; Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Greenville, South Carolina; Austin, Texas; and several locations in Mississippi. Three of these sites are located in cold-weather climates where pavements are subjected to winter maintenance activities, which could influence pavement albedo. At each site, ten locations were selected for testing. These locations encompassed both asphalt and concrete surfaces varying in age from new construction to 20+ years.

Albedo testing followed ASTM E1918-06, which requires taking measurements during the summer months between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. to meet solar energy input criteria. Cloud cover was avoided as much as possible during testing. Measurements were taken using an albedometer, which includes an upward-facing pyranometer that measures incoming solar energy and a downward-facing pyranometer that measures solar energy reflected by the pavement. As shown in Figure 1, the downward-facing pyranometer is positioned at 0.5 m above the surface and creates a scanned area comparable to the width of a standard traffic lane.

Figure 1: Leveling an Albedometer for Field Testing

Aside from pavement type and surface age, the variables expected to have the highest impact on pavement albedo are surface color, coarse aggregate color, and surface texture. These data were also collected at each location. The pavement surface color in the center of the lane and in the wheel path was visually matched with a grayscale chart. Each shade on the grayscale chart was correlated with a grayscale value from 25-255, with higher numbers representing lighter shades. For the sites evaluated in the study, an analysis of the surface color data indicated there were no consistent or practical differences between center of the lane and wheel path measurements. Cores were also cut at each location, allowing measurement of the dominant coarse aggregate color in the same manner. Pavement surface texture, expressed as mean texture depth (MTD), was measured at the center of the lane and in the wheel path of each location using the sand patch procedure. For surface texture values greater than 0.70 mm MTD, differences exist between the center of the lane and wheel path measurements. However, analysis showed that the differences should not bias the albedo model.

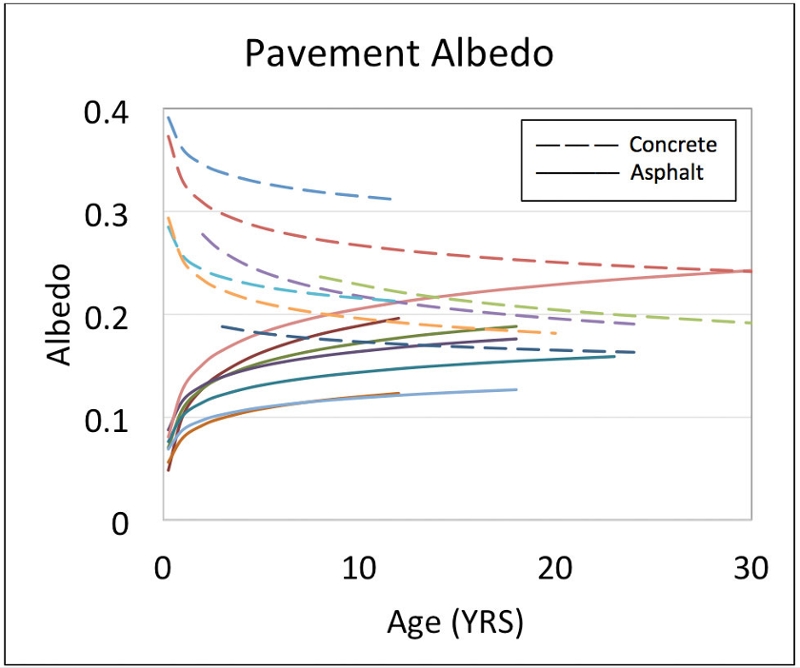

Best-fit regression curves for field-measured albedo at each site are shown in Figure 2. The plots show that asphalt pavement albedo increases over time, while concrete pavement albedo decreases over time. After 10-15 years, the asphalt and concrete albedo values begin to converge. While the albedo curves within each pavement type have a similar shape, the curve for each site is unique, and the long-term trend values are different for each site.

Figure 2: Field-Measured Asphalt and Concrete Surface Albedo Change with Time

For the asphalt albedo model, the best fit regressions were logarithmic equations in the general form

Y = a x ln(X) + b

where Y is the albedo value, X is the pavement surface age in years, and a and b are regression coefficients. Coarse aggregate color most influenced the coefficients. A predictive model for the albedo of asphalt pavements was developed, including only surface age and coarse aggregate color as inputs.

The concrete albedo model was developed in a similar manner. The best fit regressions for the concrete albedo data were power equations in the general formY = a x Xb

where Y is the albedo value, X is the pavement surface age in years, and a and b are regression coefficients. Analysis showed that surface texture was a predominant factor influencing albedo for concrete pavements. However, surface texture depends on individual job specifications and construction quality, so it is a less consistent variable than coarse aggregate color which also showed a strong effect on albedo. However, a reliable model could not be established to predict albedo using pavement surface age, coarse aggregate color, and surface texture. Further research is needed to determine additional pavement characteristics that contribute to concrete pavement albedo.