Chemical engineering senior researches hydrogels to improve space transportation

Published: Mar 6, 2025 11:00 AM

By Caitlyn Griffin

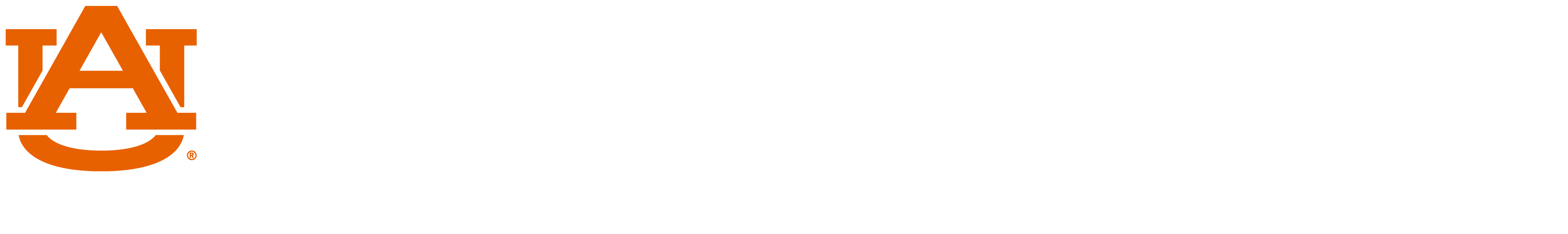

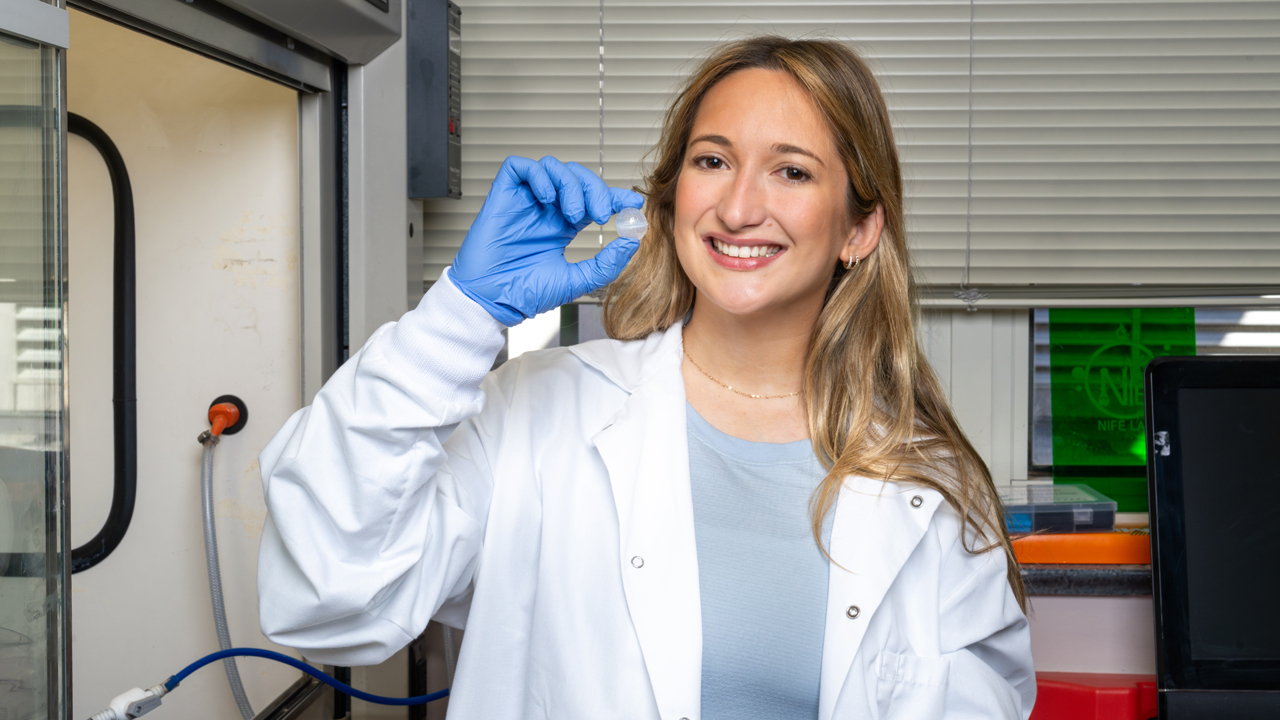

Mari Miles Dempsey, a senior in chemical engineering and an honors student, is researching photo-initiated hydrogels alongside Jean-Francois Louf, assistant professor in chemical engineering.

If successful, the project has the potential to impact multiple fields, but the most hopeful utilization is transporting items to space. Louf explained that this project was inspired by NASA's Artemis moon missions, which aim to establish a permanent lunar base in the next two decades.

"Building infrastructure on the Moon presents unique challenges, including limited resources and lower gravity, so we explored innovative ways to fabricate lightweight yet durable structures using ultraviolet (UV)-curable polymers," Louf said.

In this experiment, Dempsey developed water-soluble, photoinitiated TPO nanoparticles to create a hollow sphere by mixing them with an AP hydrogel base, 3D printing a mold and curing the mixture with UV light. After partially curing, the sphere was vacuum-expanded in a desiccator and fully hardened with a final UV cure, allowing it to maintain its expanded shape once the pressure normalized.

"The idea is that since it cures with UV light, you can place it in a vacuum before it is fully cured," Dempsey said. "Hollow shapes expand in a vacuum, so if you expand it and then cure it in that expanded shape, you can effectively make it much bigger than it was when you first developed it."

Regarding expansion, Dempsey said that since the sphere is hollow, everything is air, so the lack of pressure in the vacuum forces the volume inside to increase. The air inside pushes on the sphere, causing its growth in size.

"When we place it in a vacuum, there is no external pressure," Dempsey said. "As the pressure drops, the volume inside the sphere has to increase to maintain balance. This expansion means the air inside the sphere is growing in volume. Hypothetically, with enough elasticity, you could make it grow quite large."

However, Dempsey said, if the sphere isn’t cured and the vacuum is turned off, it would collapse.

"If we fully cure it, it becomes like hard plastic,” she said. “Once the vacuum is turned off, it stays in that rigid form and maintains its shape when removed."

The project progressed before the winter break when the sphere increased in size. So, with the small progression, Dempsey is motivated to continue this research.

"We finally got a video of it expanding just in the last month or so," Dempsey said. "That's where we are now. It hasn't expanded much yet, but we're hoping to experiment with the ratios and get it to expand more.”

As for the end goal, Louf emphasized that they weren't aiming for a particular measurement but rather proof of actuality and functionality.

"The goal of our project is to develop a proof of concept in the lab by demonstrating that a polymer with an internal cavity can expand under reduced pressure and then be UV-cured into a stable structure," Louf said. "This research could contribute to future lunar construction techniques by offering a lightweight, scalable and resource-efficient method for creating infrastructure on the Moon."

Louf further discussed how this idea would be a huge step in implementing lightweight building blocks without needing heavy equipment and excessive raw materials.

"The concept involves injecting a liquid polymer into a mold along with a gas bubble, which could be sourced from CO₂ exhaled by astronauts," Louf said. "When placed in a non-pressurized lunar environment, the gas would expand due to the low external pressure, forming an internal cavity. Once exposed to UV light from the Sun, the polymer would cure and solidify, creating a structural component with an optimized strength-to-weight ratio."

Media Contact: , cvg0007@auburn.edu,

Mari Miles Dempsey, a senior in chemical engineering (right) holds a photo-initiated hydrogels sphere next to Jean-Francois Louf, assistant professor in chemical engineering.