Assistant professor of chemical engineering earns $875K DOE Early Career Award to advance membrane-based lithium separation research

Published: Feb 11, 2026 9:00 AM

By Joe McAdory

Can lithium and other critical materials be selectively extracted from chemically complex water solutions without relying on slow, energy‑intensive methods? Absolutely… and Cassandra Porter has the membranes to prove it.

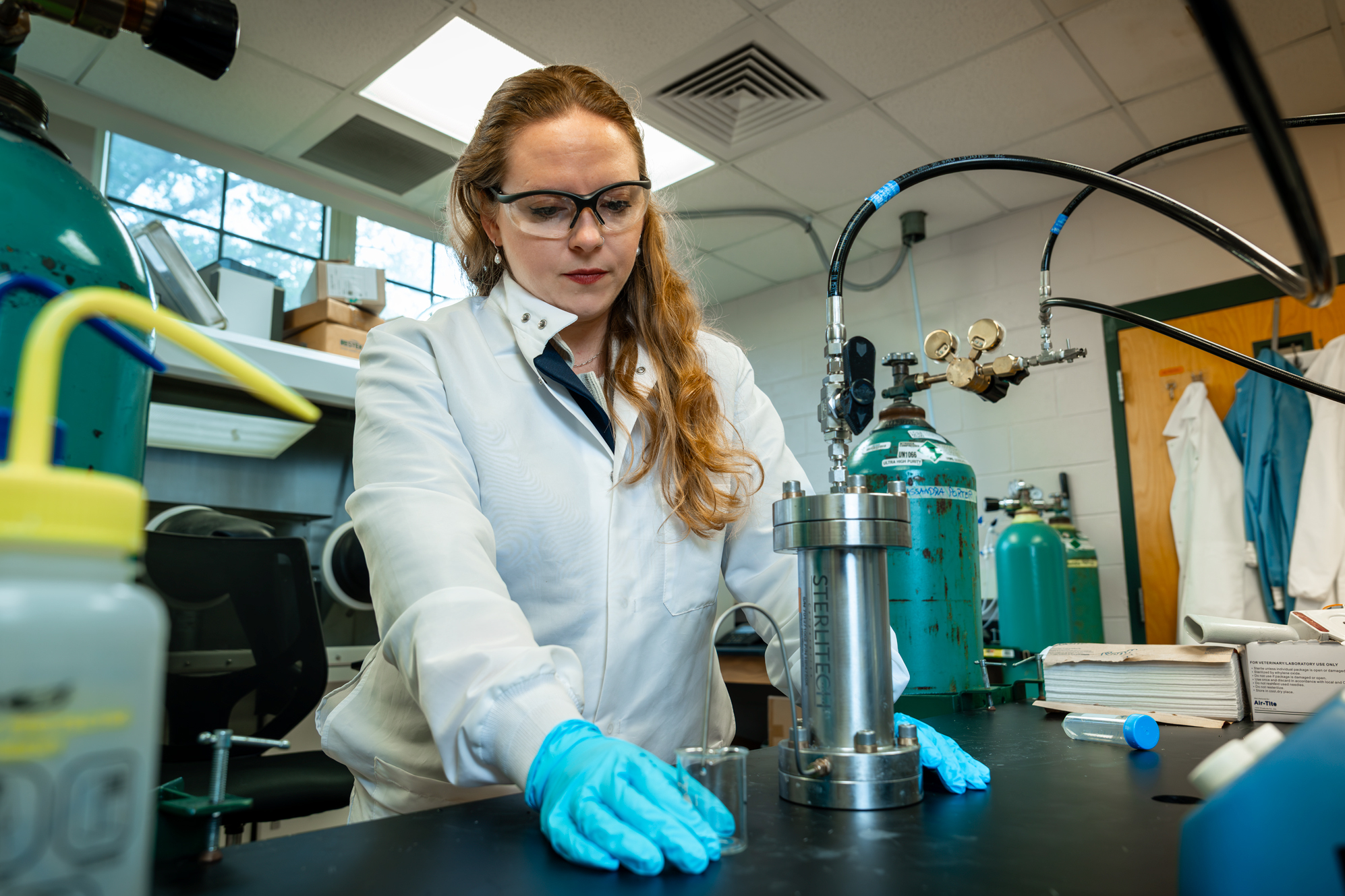

Porter, assistant professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering, was granted a five‑year, $875,000 U.S. Department of Energy Early Career Award for her project, “Elucidating Operational and Chemical Factors Affecting the Function of Novel Polymeric Brush Active‑Layer Membranes for Lithium Recovery from Aqueous Solutions.” This research will explore how membrane chemistry and operating conditions control ion selectivity under real‑world conditions.

By making it easier to separate lithium and other critical materials from water, Porter’s work could help lower the cost and improve the reliability of materials that power batteries, electronics and energy storage systems.

“When we talk about separating charged species like ions, the first question you have to ask is how are they different from each other,” Porter said. “Then you leverage that difference. Ions are similar in size and often have similar charges, so what you can exploit becomes very limited.”

Her project aims to push past those limits, and she isn’t stopping at lithium.

“This research can evolve into looking at other charged species we can recover, such as uranium, copper, gold and yttrium,” she said. “It’s about securing energy pathways that are sustainable and recycling materials, because the planet is not unlimited in its resources. You can come up with all sorts of energy solutions, but you need to make them transportable. That’s what batteries do. They let you store energy and take it wherever it’s needed.”

Department of Chemical Engineering Chair Selen Cremaschi said Porter’s work is defined by its focus on fundamental questions with real‑world consequences.

“Career awards are as much about the researcher as they are about the project,” Cremaschi said. “In Dr. Porter’s case, this award recognizes the way she approaches difficult problems — grounding her work in strong fundamentals while keeping a clear sense of where it can lead. That combination is exactly what these awards are meant to support.”

Porter is the third faculty researcher in the department to win Career awards in the past year. In January 2025, Assistant Professor Michael Howard was granted a five‑year, $500,000 National Science Foundation (NSF) Career Award for his project, “Multiscale modeling for self‑assembly of colloidal‑particle coatings with gradient compositions.” In February 2025, Assistant Professor Jean‑Francois Louf earned a five‑year, $843,000 NSF Career Award for his study, “Mechanisms of Acoustic Signal Processing for Increased Nectar Sugar Concentration in Flowers.”

Central to her project is a polymeric brush active‑layer membrane that behaves less like a traditional filter and more like a precisely engineered molecular gate. Instead of casting a membrane top-down and evaluating its performance after the fact, her laboratory group builds the active separation layer from the bottom up, growing polymer brushes molecule by molecule. The NSF recognized her research on polyamide brush active‑layer membranes with a three‑year, $303,707 award in 2024.

“The bottom‑up control is what allows us to really understand why a membrane behaves the way it does,” Porter said. “If you don’t have that level of control, it’s very difficult to parse out what characteristics of the membrane material are actually driving the separation.”

That precision becomes essential when membranes move beyond simple laboratory conditions. Brines from geothermal systems or oil and gas production contain dozens of ions interacting simultaneously, and behaviors that look predictable in isolation can shift dramatically when everything is mixed.

Porter’s research is designed to untangle those interactions through two complementary approaches. One examines how specific molecular features in the membrane impacts ion transport. The other investigates how external conditions (pH, temperature and ion ratios) reshape membrane behavior.

There are challenges, however. Lithium and magnesium, for example, are both positively charged and have similar hydrated sizes, making them difficult to distinguish. But Porter believes her team, “can strategically pull off the waters from lithium through a unique gradient structure, exploiting differences in dehydration energy to drive separation.”

Graduate students supported by the award will synthesize these specialized membranes, design separation experiments and analyze how ions move under changing conditions, a process that requires systematic testing across multiple scenarios.

“This isn't something you answer with a single experiment,” Porter said. “You have to test the same system under different conditions, look closely at what changes and then ask why those changes are happening.”

The goal: demonstrate a membrane that works and understand why.

“That's what success looks like for us,” Porter said. “Being able to say with confidence which features matter, which ones don't and how to design the next membrane based on that understanding.

“Winning this award says that they (Department of Energy) don’t just believe in the specific project you proposed, but they also believe in you as a scientist. It’s about the difference they think you're going to make not just with this project, but beyond.”

Media Contact: , jem0040@auburn.edu, 334.844.3447

Assistant Professor Cassandra Porter inspects a recently synthesized brush active-layer membrane that soaks in solvent to remove unreacted monomers and catalysts.